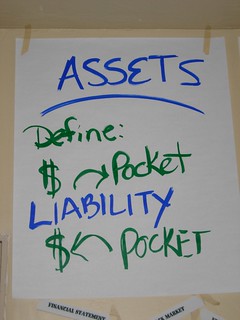

Is This Home an Asset or a Liability?

Hint: Asset earn money every month; liabilities cost.

Since about the end of World War II, Americans were told by every source they had available that their homes were one of the most important assets they would ever own. Homes went up in value over time, you see, so once you had your home paid off, every bit of value your home gained from that point onward was profit. Of course, all that was laid to waste when the public became aware of the concept of a ‘real estate bubble’ that could rip all of the value out of your home and still leave you sitting there paying a mortgage on something that wasn’t worth half of what you still owed. Nowadays, we tend to be much more careful about the homes we buy…unless we’re buying it with the intention of investing in it.

Since about the end of World War II, Americans were told by every source they had available that their homes were one of the most important assets they would ever own. Homes went up in value over time, you see, so once you had your home paid off, every bit of value your home gained from that point onward was profit. Of course, all that was laid to waste when the public became aware of the concept of a ‘real estate bubble’ that could rip all of the value out of your home and still leave you sitting there paying a mortgage on something that wasn’t worth half of what you still owed. Nowadays, we tend to be much more careful about the homes we buy…unless we’re buying it with the intention of investing in it.

For some reason, there are millions of Americans who believe that an investment property is allowed to be worse, somehow, than one they would buy and plan to live in for the rest of their lives. The problem is that, as many people have since learned, some houses are assets — they generate value over time — and others are liabilities: they consistently cost more than they bring in, season after season, year after year.

The Renovation Fallacy

The ‘liability class’ of homes still gets purchased regularly by investors on the assumption that a cheap home can be turned into a solid investment through the magic of renovation. And on paper, this is true: any home can become profitable, given enough money poured into it and enough time passing. The problem is that these investors often vastly underestimate just how much money (and how much time!) it can take to turn a liability-class home into an asset. When you get to the point where you’d be spending less money if you purchased an empty property and built a new house, your property is an objectively bad investment.

Running the Numbers: The Really Basic Edition

To figure out whether a given home is going to be an asset or a liability, you need to calculate two numbers: the cashflow, and the RoI.

Calculating the RoI is pretty straightforward: it’s the number you get when you divide your final equity gain by the total of all money spent to get the home into its current state. For example, if you purchase a home for $50,000, and then you spend an additional $150,000 renovating and upgrading, and you end up with a home valued at $250,000, you just spent $200k to get a $250k home. That makes your equity gain $50k. Dividing your equity gain by your total cost ($50k/$200k), you get an RoI of 25%. That’s great! A 15% RoI is the turning point at which most homes stop being worth the amount of time it takes to do the work — as long as you’re beating that, you’re doing well.

The RoI is, however, only a calculation of the degree to which the home increases your net worth as an investor. What really matters in terms of your ability to maintain and profit from the home is the cashflow. To do this, you first have to add up all of the monthly costs of owning the home, including:

- Property Taxes,

- Insurance,

- Property Management fees,

- Mortgage payments,

- HOA fees,

- Losses to vacancies,

- Losses to repairs/maintenance, and

- Any other relevant recurring costs.

Generally speaking, it’s common practice when you’re getting started to estimate Property Management fees at 10% of the intended annual rent, Losses to vacancies at 10% of the intended annual rent, and Losses to repairs/maintenance at 20% of the intended annual rent. These numbers are all slightly on the conservative side, but that’s a good thing.

Once you have all of the monthly costs added up, you have to subtract that number from the intended monthly rent. If you end up with a negative number, you’re in trouble. If you end up with a positive number, you need to do one more calculation to determine if the home is an asset or a liability, and that is to determine the ‘capitalization rate’ of the home.

The cap rate is determined by taking the annual expected profit of the home (the cashflow number x12) and dividing it by the total of all money you spent to get the house to rent-ready, which we calculated already above. So to continue the example from above, if your 25%-RoI house took you $200k to get rent-ready, and your annual expected profit is $12000, your cap rate is ($12k/$200k), or 6%. That’s a really iffy investment — 6% cap rate is right on the border of what most investors would consider acceptable for a rental home. 8% is the standard ‘good enough’ number for single-family residences.

And that’s it! If your RoI is solid, your cashflow is positive, and your cap rate hits the 8% standard or better, you have a genuine asset on your hands — now get a good property manager, sit back, and reap the rewards!